Small Places Loosely Joined

Wed 23 September 2020 by Jim Purbrick

Over the last few years I’ve spent a lot of time helping people new to virtual worlds learn how they work. Over the next few weeks I’m sharing a series of short posts on some of the high level concepts I covered which will hopefully be useful to other people new to virtual worlds. The previous post talked about how you can make sure everyone can create an avatar representation that they feel properly expresses them within a virtual world, this post talks about how you can structure the world so that everyone can move around easily to find everything that they want.

Second Life always aspired to be the Metaverse, but in the beginning it was more like a neighbourhood. The first regions were named after streets in SoMa and, like the district in San Francisco, people took walking tours from one corner of the world to another, flew biplanes across the sky and sailed on the simulated winds around the bay. However you decided to travel in the early days you could see the whole world in a few hours, so Philip Rosedale became very excited when he realised one day that the constant tsunami of content generated by Second Life’s residents had grown so large that the world was changing too fast to see everything.

As the Second Life continued to expand and change at an ever faster rate it became increasingly important to have ways to find the good stuff. Bookmarks, searches and external blogs indexed the expanding world helping people find things. Rather than walk, fly or sail around the world people would teleport from place to place or event to event. Even if you wanted to walk it became increasingly hard to do so: more and more parcels of land became private, restricting entry to both people and any scripted fish unlucky enough to try to swim across the boundary.

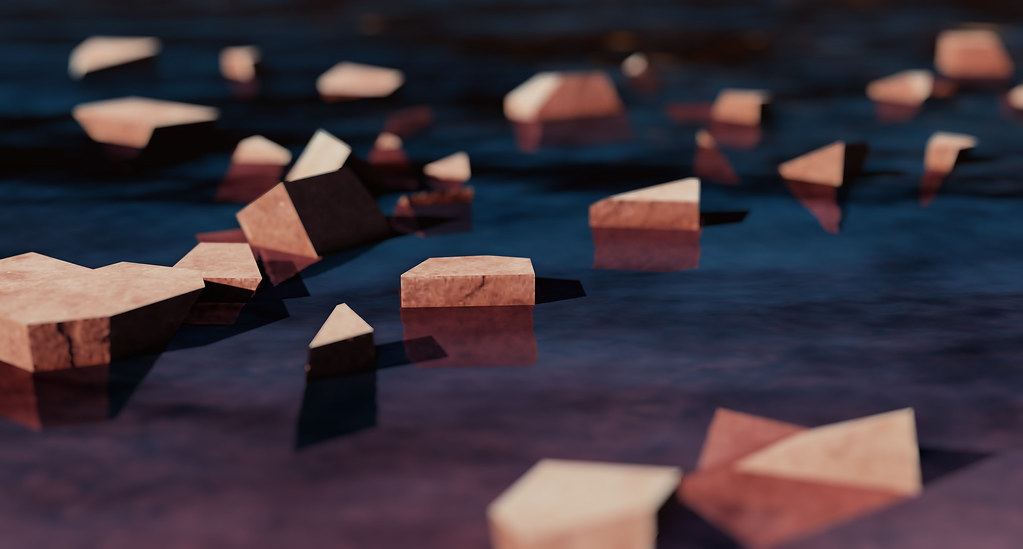

While you could still plot every parcel on a map which grew to the size of Denmark and looked like a huge series of fjords, as more and more people wanted a beach front property, the world effectively became a graph of experiences which people teleported between. The seamless, endless world that descriptions of the Metaverse conjure up and that Linden Lab aimed to build ended up being a graph of bite-sized experiences linked together like a web.

Technologically, Second Life also began to split at the seams. The addition of Second Life URLs (SLurls) allowed blogs to link to locations in Second Life and people increasingly wrote scripts which published out to the web and Twitter or pulled data in from the web to visualize in 3D. A lot of people would keep a browser tab open showing the presence information published to the web and would teleport to their friends as soon as they saw them come online. Developers wrote applications on web servers which used Second Life scripts just to build user interfaces so they could escape the limitations of the in-world scripting platform. People captured 3D geometry sent to their graphics cards to provide 3D printing services or circumvent in-world DRM to produce knock-off virtual goods. Companies like IBM lobbied Linden Lab for legitimate ways to host their own private regions while open source developers forged ahead to produce alternative clients and servers that anyone could run. Despite much concern, these efforts mostly provided developers with more convenient development sandboxes: the content, community, conversation and commerce stayed on the Linden Lab hosted grid.

Towards the end of my time at Linden Lab there was a push to standardize these efforts and make it possible for experiences run by different organisations, potentially on different technology stacks, to inter-operate. For people to teleport not just between regions, but between organisations taking their appearance and inventory of clothes, animations, and interactive objects which defined their identity with them. This was a big deal, so it was incredibly encouraging to see some of the earliest experiments in social VR at Oculus try something similar by linking Oculus Rooms to other experiences via coordinated app launch (CAL). While the first CAL implementations linked Oculus Rooms to a fixed set of published experiences it’s easy to imagine people using similar technology to build environments which link to their favorite locations around the Metaverse just as early web sites curated links to favourite content around the web.

When we think about the Metaverse it is easy to jump to images of endless wonders teaming with multitudes stretching to a distant horizon. Linden Lab dreamed similar dreams and went to extraordinary lengths to make Second Life appear seamless, but much of that effort could have been more profitably spent enabling a universe of small places, loosely joined. Several social worlds that followed Second Life including Metaplace, Whirled and Linden Lab’s own Sansar all learned this lesson by building collections of linked experiences rather than a single space containing everything. Linking experiences also makes it easier to support requirements like IBM’s need to host their own servers, build experiences which require custom clients to support new or specialized hardware or weave existing applications which may have been built on different engines into a broader Metaverse. As we think about building new Metaverses, it’s important not to just think about how we can bring everything into our worlds and make them stretch out to infinity, but also about how to connect experiences and technologies together and allow people to move and connect between them.

(Second Life screenshot: Ella Pinellapin)

The Creation Engine No. 2

The Creation Engine No. 2